Traveling with the Wounded: Walt Whitman and Washington's Civil War Hospitals

by

Traveling with the Wounded: Walt Whitman and Washington's Civil War Hospitals

by

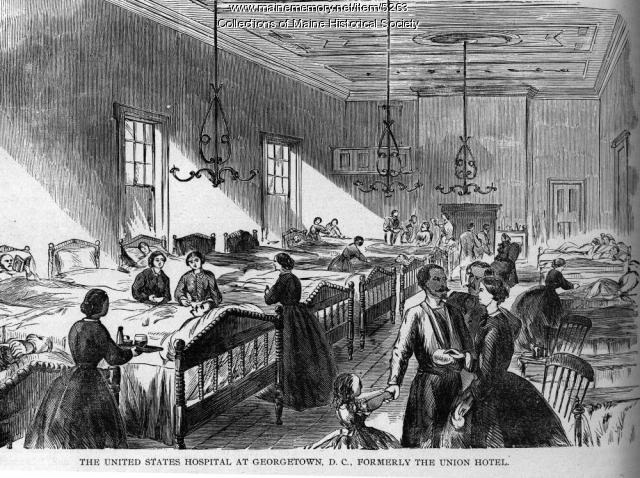

U.S. Hospital, Georgetown, D.C.

by

U.S. Hospital, Georgetown, D.C.

by

Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse

by

Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse

by

The first thing I met was a regiment of the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose, and took it by storm. Cologne, with its seven and seventy evil savors, was a posy-bed to it; and the worst of this affliction was, every one had assured me that it was a chronic weakness of all hospitals, and I must bear it. I did, armed with lavender water, with which I so besprinkled myself and premises, that, like my friend Sairy, I was soon known among my patients as "the nurse with the bottle." Having been run over by three excited surgeons, bumped against by migratory coal-hods, water-pails, and small boys, nearly scalded by an avalanche of newly-filled tea-pots, and hopelessly entangled in a knot of colored sisters coming to wash, I progressed by slow stages up stairs and down, till the main hall was reached, and I paused to take breath and a survey. There they were! "our brave boys," as the papers justly call them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name with an uncomplaining fortitude, which made one glad to cherish each as a brother. In they came, some on stretchers, some in men's arms, some feebly staggering along propped on rude crutches, and one lay stark and still with covered face, as a comrade gave his name to be recorded before they carried him away to the dead house. All was hurry and confusion; the hall was full of these wrecks of humanity, for the most exhausted could not reach a bed till duly ticketed and registered; the walls were lined with rows of such as could sit, the floor covered with the more disabled, the steps and doorways filled with helpers and lookers on; the sound of many feet and voices made that usually quiet hour as noisy as noon; and, in the midst of it all, the matron's motherly face brought more comfort to many a poor soul, than the cordial draughts she administered, or the cheery words that welcomed all, making of the hospital a home.

Hospital Sketches (1863). Louisa May Alcott’s letters home during her Civil War nursing experience became her first modest success. The Boston Evening Transcript called the book "fluent and sparkling, with touches of quiet humor and lively wit." Her father Amos Bronson Alcott predicted the sketches "likely to be popular, the subject and style of treatment alike commending it to the reader, and to the Army especially. I see nothing in the way of a good appreciation of Louisa's merits as a woman and a writer. Nothing could be more surprising to her or agreeable to us. Alcott was indeed surprised when Hospital Sketches was well-received: "I cannot see why people like a few extracts from topsey turvey letters written on inverted tea kettles, waiting for gruel to warm, or poultices to cool, [or] for boys to wake and be tormented" but "I find I've done a good thing without knowing it."

Read Hospital Sketches online at:

Image courtesy of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House/

L. M. A. Memorial Association

During the Civil War, Confederate military medical authorities

established general hospitals behind the lines in at least thirty-nine

cities and towns in Georgia, though many of them remained at a

particular location for only a short time. (New Georgia Encyclopedia, Confederate Hospitals.)

During the Civil War, Confederate military medical authorities

established general hospitals behind the lines in at least thirty-nine

cities and towns in Georgia, though many of them remained at a

particular location for only a short time. (New Georgia Encyclopedia, Confederate Hospitals.)

Wounded from both sides were brought into Rome for treatment. Hospitals were set up in churches and many of the buildings on Broad Street. In May, 1864, Rome fell to Federal forces under the command of General William T. Sherman. Federal troops occupied Rome until November, 1864. When General Sherman and his men departed they set fire to many of the buildings, sparing only those in use as hospitals.

First Presbyterian Church, dedicated in 1856, was used by Union troops for food storage and reportedly as a hospital during the Civil War. The pews were removed and used for the construction of a pontoon bridge across one of Rome's rivers and for the construction of horse stalls.

In Cave Spring, Fannin Hall, the original administration building of the Georgia School for the Deaf, was used as a hospital and it was here that Missouri boys of the famous “Orphan Brigade” were treated following the battle at Allatoona Pass.

In Lafayette, The LaFayette Presbyterian Church was used as a field hospital by both armies.

Eli Pinson Landers was nineteen years old when he left his home in Gwinnett County, GA to join the Confederate Army in August of 1861. In his frequent letters to his mother, Eli describes the excitement and adventure of going off to war and his passionate dedication to the Southern cause. But as time goes by, his letters become more serious, describing the hardships of life in a military camp, watching his companions die in battle and from disease, and other horrors of war, such as having to dine among the dead. As he falls ill and writes his final letters home, he tells his family how he wants to be buried and what words to inscribe on his tombstone. On October 16, 1863, Eli Landers died of typhoid fever in the hospital at Rome, Georgia. (The Civil War in Georgia, Letters of Eli Landers.)

Kate Cumming spent much of the latter half of the Civil War as a nurse in hospitals throughout Georgia. Inspired by both the Reverend Benjamin M. Miller, who in an address urged the women of Mobile in early 1862 to aid wounded and sick Confederates, and by Florence Nightingale, the heroic British nurse who served in the Crimean War, Cumming, despite having no formal nursing training, decided to offer her services. Much to the distress of her parents, who firmly believed that ladies did not belong at the battlefield, she left Mobile in April 1862, along with forty other local women, including the novelist Augusta Jane Evans (although Evans did not make it to the front), for the Mississippi-Tennessee border. Unlike most women nurses, who served only temporarily, Cumming continued as an active nurse for the duration of the war. (New Georgia Encyclopedia, Kate Cumming.)